Episode highlights

- 00:01:45 – Zsuzsa’s Background in UX

- 00:05:56 – Problems with Surveys

- 00:10:29 – Why Interviews Are Better

- 00:23:06 – Handling Stakeholder Expectations

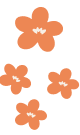

About our guest Zsuzsa Kovacs

Zsuzsa is a Freelance Lead UX Researcher, who has worked in UX since 2008. She tried many different roles around building products but in every role her main focus was involving users in the process early on and keeping them close. She enjoys talking to people, seeing products through their eyes, understanding their point of view. She is interested in psychology, especially areas that affect research. She is a co-organiser of the Amuse UX Conference.

Mentioned articles

Podcast transcript

[00:00:00] Tina Ličková:

Welcome to UX Research Geeks, where we geek out with researchers from all around the world on topics they are passionate about. I’m your host Tina Ličková, a researcher and a strategist, and this podcast is brought to you by UXtweak, an all-in-one UX research tool.

This is the 43rd episode of UXR Geeks, and you are listening to me talking to Zsuzsa, a freelance UX researcher. If you would be looking for a UXR superstar coming from the central European area. It would definitely be Zsuzsa. And by this, I don’t want to diminish her professionality, but she’s definitely somebody with a great experience starting in programming, then transferred to UX design, then starting to focus on the biggest passion, which is UXR research.

And she’s a great speaker who has a lot of important things to say. Like in this episode, Zsuzsa is advocating for using surveys very wisely or not using them at all, if possible, because she thinks there are many other important methods and methodologies, how we can really get close to users and their needs.

Tune in and learn because there’s so much to be learned about.

Tina Ličková:

And I’m happy that we have a Central European superstar in the podcast.

Zsuzsa Kovács:

Oh my God.

But for the people who might not know you, who are you, what are you doing? So we have a little bit of context.

[00:01:45] Zsuzsa Kovács: So I’m Zsuzsa Kovács. I’ve been working as a UX researcher for a long time now, but I did almost everything in IT so far in my career.

I have a background in, in MA in computer science. I studied programming. So I started off as a developer, but pretty fast, I realized that’s not something I want to do in the long term. And I switched over to UX design. I had a pretty cool employer who actually supported it totally. And then, uh, to learn more, I even moved to the German center of the company.

Actually, it was SAP and I studied UX design there. And became a UX designer. And then I, when I came back to Hungary, I joined Prezi and I spent the last almost 10 years there of my career. And in the last year, I worked as a freelance UX researcher. And at Prezi, I also tried, I was a manager of the UX research team for a while.

I also tried out myself as a product manager. So I actually really tried the many different roles in product development. But research is where my passion is, let’s say. Where does this passion come from? I really think good products can only be built if you talk to the people who are going to use it or who are using it.

So I really think that good products or valuable products are ones that are solving a real problem, something that people have every day. And that’s what It solves it in a way that is familiar for them and that is easy to use and easy to understand. And I think to reach that, first of all, you need to understand the problem.

So that’s where discovery research comes in. And then you need to validate your ideas because you can be the smartest people, but if you’re looking at something for a long time, you won’t see the problems and the biases after a while or the issues with it. So you need to show it to people. So my passion is, I totally love usability testing.

That was actually the first professional training that I got in research or in UX design. And I still think it’s an amazing tool to discover problems and issues. Yeah. So I tried many different aspects of product development, and I think I’m the best when it comes to being the advocate for users.

[00:04:01] Tina Ličková: When we were preparing and I’m looking into our notes, I like the sentence that you’ve wrote there that I don’t believe in heuristic evaluation expert reviews, and this is what got my attention because we were also talking about that we want a little bit provoke with this episode, so please.

Provoke the shit out of it if you want to.

[00:04:25] Zsuzsa Kovács: Good, good. If you have a new product or you have a product that no user have ever seen before, it has not been tested, it has not been researched, you most probably can get a lot of value out of an expert review if it’s done by really experienced UX researchers.

I don’t, you know, that if you look at a product, we cannot see. The problems with it, but every time I look at a product and I think I know what the problem is, then I do some usability tests and I’m, my mind is blown because there is no way you can come up with all the amazing ways users misunderstand the interface.

That, that you are looking at, because I think as every developer and everybody who’s working on products, we are tech savvy people, and we are used to certain things, and so we cannot even think with the head of someone who is not so tech savvy or coming from a very different background, having experience in a very different field, for a long time now, when I’m.

Asked to evaluate a product. I don’t even walk around in it too much. I have asked for an expert to help me with, to come up with the usability test tasks. I let users discover it. And I love to discover, I love to discover a product through the eyes of users. It’s always much more valuable and yeah, sure, some of my hypotheses will be, of course, approved.

There’s so much more they will find problematic in it. So that’s why I believe, sure, you can discover some issues, but you will never be able to discover every issue that is in there.

[00:05:56] Tina Ličková: And this is where it connects to one method that you. I don’t want to use the word hate, but maybe it’s appropriate in some ways that you really dislike surveys.

Why is that?

[00:06:11] Zsuzsa Kovács: Yeah, so I have a very complicated relationship with surveys and the reason is that I really think good research. As I just explained it how usability test works, that you have some hypotheses and if you do it right, it actually opens up this world of problems that you thought in the beginning.

And the same when it comes to discovery research, I think good research is that you start with like a hypothesis or some understanding of the problem space. And as you talk more to more and more users, the problem space is opening up. And if you have users or you have the right questions in your interviews, for example, and you can get people who tell you stories, suddenly you realize that it’s a much bigger problem area or problem space than you ever imagined.

And this is what surveys will never do. Make a survey in itself by design are a very leading way of doing research because you not only define the questions, you also define the answers. And so, this actually blocks it from really being able to realize what else is also part of this area that you try to understand.

One of my favorite researchers in the area, who is not known by so many people, but she is my heroine because she always talks about, and in a very provocative way as well, um, about like the bad methods. And she’s Erica Hall, and she even created a very small leaflet a few years ago, which is about why surveys are bad, why we shouldn’t do surveys.

And she’s calling this method, and I really love the way she described, she’s calling it an attractive nuisance. And it’s, this term is coming from law, and it means they call an attractive nuisance, something that seems very good to do. But it’s very dangerous. So her example was a pool, you know, for a kid.

It’s very lacking. They would love to go there, but it’s very dangerous for them. And this is surveys in research because it looks like everybody thinks they could do a survey, right? And I think by the surveys that come, we come across every day, it seems that everybody’s doing it without having the real background and without understanding what are the thousands of ways you can actually bias your own research.

Without even realizing, because you know, like you can ask the bad, like bad questions and you can set up bad answers. And then what you will do is only basically approve your wrong preconceptions, never realizing that you manipulated the whole thing. So that’s why I really think it’s a problematic thing.

Uh, and it’s also, so too available. So since, uh, Google Forms is out there, anybody can do a survey for free. It even analyzes it for you, which is even more dangerous in many ways. And so it’s too easy to set up, too cheap to run. And it’s at the end, it will bring you numbers, which everybody, every stakeholder is obsessed with numbers.

So unfortunately, a lot of the stakeholders are not educated enough to understand how qualitative research works. Somehow they are always, they would always go quantitative, which is super important, but I think the two together are really powerful. Just one or just the other will never do the job. So they always want to have numbers and it’s very, you know, like, surveys seem like the best way to get.

Both quantitative and quantitative results, when in fact, they will add numbers to your preconceptions most of the time. It’s the opposite of what research should be. So it’s not opening up anything. You will not learn any new things. You will only see it as something that is approving all of the hypotheses you had.

So this is what I usually see. And there are so many bad surveys. Uh, a few years ago. It was actually my hobby. And before, you know, everybody asks you to fill in the survey. Anytime I’ve seen a survey, I was filling it in and there are so many bad surveys out there and still, and even big companies are doing terrible things in their surveys.

And I wish more researchers would say, no, I’m not going to do your survey. I want to do 10 interviews instead. And I. Bet you will learn much more from 10 interviews than from a survey of I don’t know how many people filling it in.

[00:10:29] Tina Ličková: I have now not even 100th but 200th questions. And I will go back to a few of them.

You just said in the last part is really striking me because yes, survey are a syndrome of the culture that we have in company that is really important to verify that you are right. Even if you’re wrong, but to verify that, what do you think is right? This is something why I’m trying sometimes. And I know a lot of people do it as well.

When people approach you as stakeholders to do research, to ask them what they really want to learn, what they not want to just verify, but what they really want to learn. So what you are mentioning is also a lot of, and you can disagree with me, of course, but it’s a lot about the corporate culture and the willingness to really learn about the users and customer. Is there any situation where a survey is a good idea?

[00:11:25] Zsuzsa Kovács: Of course, surveys can be a good addition to your research, but I would never dare to run only a survey as research. So I think that’s the most dangerous part, but I think all of us who did the learn, like bigger researches that you do.

10 or 20 or even 30 interviews, after a while, you do start to hear patterns in the answers. And I think that’s a really, that should be the signature of, okay, now we have even enough feedback to set up a, like a survey where at least we can list the most common answers because we’ve heard each of these like several times.

And if you do that, you already did a lot to, to set up a good survey because you did your research before and you’re not starting it blank. But the most dangerous thing is when you don’t have, when you haven’t done any kind of research before setting up the survey, then you really will only list your hypothesis without even thinking how different answers can be out there.

And one thing also that people should understand or researchers should understand because they can say, sure, but we always put there the other like option as an answer. But You should also see that now people are also current out of surveys. You know, you, even if you buy a toothbrush, the company will send you an email to evaluate the toothbrush.

And these are actually surveys. They will want us to give our opinion on a topic in a written format or in a survey format. So we are a bit burnt out and I just run actually a bigger survey recently, which was not the first, you know, we had a few deep interviews about e commerce and then we did a survey and people are not typing in answers.

So that’s the other thing. Even if, you know, your options are not really covering their answers, they are not going to write there, you know, like a novel of how they think about it, what you could get in an interview if you ask them, but they will just answer you in three words. And what re what it resulted is I just wanted to ask more questions, but that’s not really an answer. So people are burned out. They will not really spend much, a lot of time with your survey. They will just, they just want to get over with it. That’s their motivation. And they will, they, it’s not the same as when you ask them to dedicate an hour and you are asking them and you can ask extra questions and you can clarify things when you don’t understand.

It will never be that. So it, it just looks like you get a lot of answers and you get the opinion of a lot of people. But in fact, they just, they really just select something to get over with it and then finish it.

[00:13:59] Tina Ličková: I like the idea of survey fatigue. That’s a strong one, in my opinion. So if I should paraphrase, it’s if we did enough research and things are trying to starting to repeat, you can verify with a survey or have offered the answers that we think that are coming up.

I’m wondering if starting something with a survey and then continuing, of course, not just relying on the survey, would it be, in your opinion, a good idea?

[00:14:28] Zsuzsa Kovács: I would never start with a survey. I think at least an ethnography should be done before. So you have a better understanding of the context, except you are researching the area for, I don’t know, long years.

Then, sure, you have a basic understanding, but if the area is totally new, if the domain is totally new, I think it’s very dangerous to start the survey. But if you do ethnography there, at least you come see other people’s perspectives. And I think you already can step back and say, Yeah, maybe, maybe I can’t come up with all the answer options to this question and maybe you decide to make it an open question because, you know, that again opens up a little bit.

You don’t bias the whole survey that much, but as I said, people will not write down in detail what they think about the question. If it’s not mandatory, they will step it over and not type because I think most of the time they are also doing, are filling in surveys on a mobile phone, but yeah, at least an ethnography, they do at least an ethnography, but I think.

The good, uh, order is you do some interviews. And what a survey can add to that is that maybe you met three people who said one thing and just two who said the other. But when you do a survey with the same answers, it might turn out that the two were actually the representing the majority of answers. It was, you know, just in your way of finding, uh, interview participants, it happened a different way.

So now this big research that I just did, And we did deep interviews and surveys. Again, unfortunately, it proved my bad feelings about surveys because we didn’t learn anything from the surveys. But it was amazing to see that like 10 deep interviews, or I don’t know, 14 maybe in total. And then we had a few answers in the survey.

And it basically only approved what we learned from the interviews, but it’s so much more colorful, everything that we learned through these interviews that I always would go for interviews instead.

[00:16:27] Tina Ličková: You were mentioning also that people are not feeling out. I have a little bit different experience when we are paying good money.

to the people for filling it out through, for example, a recruiting agency or a platform. But I am, I would say I am a little bit scared of dangers that might come with the written text. Do you see any dangers there?

[00:16:50] Zsuzsa Kovács: Sure. You know, there are even these drawings of, I just seen one recently that is what is in your, or what you believe about this topic.

This is what you can actually frame. And this is what the other person understands from it. And I think in a written format, it’s even worse because. Of course they try to express themselves in the minimum amount of words because nobody likes typing, especially not on a mobile device. So, yeah, I think one issue is that you might misunderstand each other and there’s no way to recover from that.

They might misunderstand your question. You might not fully understand what they wrote as an answer, and there’s no way to ask back. There’s no way to, to give context. So I think this missing context is one of the most painful part of surveys is that You have one chance to shoot your question the best way, and they have one chance to write it down in a way that they hope you will understand, but they will not talk about the extra, the fine grained things that might also be interesting from your research point of view.

So I think, yeah, written format is always problematic. I think it’s easier to misunderstand than when you talk to somebody.

[00:17:58] Tina Ličková: I can’t really cite the quota study, we are not really wired for written communication. And in our chatting forums, we sometimes get into small fights because we don’t understand each other.

We don’t have the intonation. And there are these hilarious videos of two friends talking to each other and one is getting Super pissed off when the other one is like super chilled. This is a situation that happened to any many of us now switching to the stakeholders because I think everybody struggles and I can tell you just five situation out of.

Where I was like, please don’t do this survey or let me just look at a survey that I damage control in its worst scenario or looking over a survey product manager and friend of mine did. And he was super excited because it was fast. But then I was like crying over the analysis until I gave this. It’s an indication and some of the things landed well, where he understood like, oh, okay, that’s why you were telling me it’s not a good idea to ask it like this and to rely on the results.

And I always say interviews are the art of conversation, surveys are science. So it’s really hard to explain the science. Tell us, how do you deal with this? Because I think everybody will be happy for some recommendation and advices.

[00:19:22] Zsuzsa Kovács: I think what you just mentioned, it’s key. When you said that when some of your friends or people you know set up a survey and then you explain them, you know, why that is a bad question.

And I think we should do that before someone shoots the survey out. And so what a lot of, what I think very few people are doing. Because everybody feels so confident about surveying because it seems so easy. It’s just a question and some answers and that’s it. So what we should do more often is get the survey reviewed by someone else, by another researcher, or if it’s, uh, yeah, done by marketing, they should ask researchers to look at it and tell them what they think about it.

But you mentioned stakeholders. And what I feel is that Many of the stakeholders who are now running big companies are actually, they started their career when UX research was not really so widely available. So they grew up with marketing research methods and that’s why they always, when they request for research in their mind, most of the time, they think of surveys and focus groups, that’s what they, that’s their way of thinking about research.

So I think when a stakeholder is asking for a survey, they’re Maybe you should ask back what you just said, mentioned earlier, what do you want to learn from this research? And then maybe explain them why the same goal can be better achieved with another method, with running a few interviews, with running, yeah, also instead of focus groups, running a few interviews or do, um, I don’t know, maybe a diary study, which is, I think, an amazing method and is very rarely used, although it can be amazing.

So I think we need to educate our stakeholders. And we need to make them better understand what are, I don’t say surveys are never good. There are good applications of them, but a big research should never only rely on, on surveys. So that’s one, one thing that came into my mind. And the other thing is that why stakeholders also love surveys is because they love numbers.

Somehow, I think in their head, so they are all, they all think that if a hundred survey answers can tell more than one interview, which in fact, I think it’s not true because the one interview can be really like, well, yeah, what they are missing in this, that, that one person is not a unique, like snowflake on earth who thinks totally differently than everybody else.

That one person is most probably representing a lot of other people. But they have the chance to better express how they feel about this area or this topic that you’re researching. So anytime when I’m requested to do a research and a stakeholder asks me like, are you sure 10 interviews will be enough?

It will that, will it be representative? Then I always, you know, ask, like, do you think I have the superpower to find 10 people on this planet who think totally differently than everybody else? And that usually eases them up and they realize, yeah, that’s right. Yeah. Probably you can’t. If you find the right people, if you don’t, you do always interviews with your friends, but you really.

Just find the people from the domain who are good representatives of the topic, then I think, and you explain that to your stakeholders, maybe they can overcome that. And even if they want numbers, because I don’t say numbers, as I said, it can actually put the priorities in a different place where you thought they are.

That’s something that surveys can help you. If a stakeholder asks you to do a survey, you only should, like, Somehow, make a deal so that you can do a few interviews before you run the survey. And I think the two together will be much more than just one or the other. But if you can do only one, I always vote for the interviews.

[00:23:06] Tina Ličková: Mm hmm. One of the arguments that comes from stakeholders is that a survey is fast and interviews take time. Is there any kind of reaction you are using in case like, Oh, but this is slow?

[00:23:22] Zsuzsa Kovács: I think people who think surveys are fast are the ones who never analyze the survey, because if you did with a two, 300 response there, you have at least five open questions.

I think they, they disagree. I think analyzing a survey. Can eat up so much time and it’s, it’s not the most delightful thing, especially if you do it right. And you do the data cleaning and you don’t rely on the terrible pie charts that Google form generated for you. And you really look into the data.

It’s not fast. It’s not fast, but yeah. I also understand that stakeholders want to, like, they want to do decisions immediately, but of course they’re not sure about that, so they want to back up, back it up with research, but it’s, it doesn’t work that way. But I think a good answer to this is that, yes, research won’t happen, good research won’t happen from one day to the other.

But development is even slower. And if you don’t do your research, you might develop at the end something. When you think about the development cycle, writing code is always the longest part because that’s when it turns reality. So if you don’t do the research and you don’t do the prototypes and the validation beforehand, then the longest part of the development will be like a failure at the end, because you will do something that nobody will understand, or it won’t solve the problem or et cetera.

You need a few weeks to run a proper research. But it’s always better to run a research even if you need to wait a few weeks and then do the right thing, then doing the wrong thing and then fix it.

[00:24:55] Tina Ličková: Maybe I have a one thing that I also tried. I let the stakeholder to run a survey that I reviewed and that interviews and we compared the results.

Of course I am treating my stakeholders with respect and those are colleagues who are experts in other fields. But I was happy about the punch in the face. That he got with my results, with my interviews. Another thing, and we will link to the article from you on Medium, you collected five plus one problem areas of surveys, which I find a great summarization of those are the total no go’s.

[00:25:35] Zsuzsa Kovács: Yeah. I wrote that like many years ago and still I meet people sometimes referring back to that article, which means maybe I should write more articles or just surveys is really an interesting topic to go what not to do with it. And yeah, from that hobby of mine, when I was filling in all the surveys that I came across, I realized that there are probably five plus one big problems with surveys in general, I would say number one is when survey is your exclusive research method, or you don’t do the interviews or at least an ethnography before, and you rely only on that. And I explained in depth why this is a problem. The second problem I, I collected it or I summarized it as bad questions. So there are still a lot of surveys and not just surveys, I should say also interviews.

So this also relies on interviews. If you have bad questions, you will get bad, you will learn the bad things. So bad questions, what I mean about that? I think bad questions are. Of course, there are the typical ones, the double barrel questions and the closed questions and the yes no questions, which you should never ask in research.

But I also often come across with conditional questions. It’s still something that is not dying out. Would you do that? Would you buy this? How much would you pay for that? All the answers to these hypothetical questions are only speculations. This is something very, very hard to answer. to get through, and sometimes, somehow people don’t stop asking these.

Then the third big problem area is bad answers. So I think the most common is when you don’t list the answer that the respondent would like to reply to, and then if it’s a mandatory question, all they can do, and there is no other, what they can do is Choose from the not there answer options one, and then it buys all the other replies because you know, it will overemphasize something that is not true.

Most probably this will be the first answer option, or when there are too many or too complicated answer options, that’s usually not good cases either. The fourth problem area is when. The, this missing context that we also discussed that I don’t understand what they are writing. They didn’t really understand my question.

Like we can misunderstand completely each other. For this, a good solution can be if you test your surveys, that’s actually like, so at least you can take out some of the questions that are easy to misunderstand. So if you can also get users and just go through your survey and you like double check if they understood the question, double if the, their answer like option is among the listed ones and so on.

Okay. The fifth problem area is biased respondents, and that’s also something I already mentioned. It’s this, we are all burned out of surveys because there are so many, all the, the NPS that you even get on like SMS messages to evaluate everything, to give feedback. And it’s on one hand, it’s a great thing that everybody would like to like evolve and they are asking users feedback, but I think it’s also overdone several times.

And what I also mean by. Okay. By sampled or by a sample is that what we experienced at Prezi until we still had a quarterly running product survey, which asked the users to evaluate certain features and what they are missing and what they like and so on, was that first of all, the fill out rate was.

Terrible. And it’s got, and it got worse, you know, quarter by quarter. At the end, it was so far from representative that we actually even stopped doing that. And the other thing we experienced that most of the time, the people who filled it out were the ones, like we call them the fans and the haters.

Somebody who loved the product and they gave five stars to everything. Honestly, you don’t learn anything from that. Sure. It’s good to see, but it’s not something you learned from. And haters are the one who just run into it. Terrible like bug where they lost the presentation or something terrible happened and then they will write their review with their middle finger.

So they are super angry and you know, that’s again, not representative because so every time there is a too strong emotion behind a feedback or an evaluation that can be misleading a little bit, so it’s not. Not necessarily the thing you’re looking for when you are running a survey. So, you know, it’s, but the worst thing is that you never know where the people who are filling it out, like, um, unless you pay for them and you can actually select who you want to fill in your survey, when you’re sending it out to your users or to your subscribers, to your newsletter, you never know who are the ones who are clicking into it, actually, and so that’s the bias sample.

And the plus one was the biased analysis, which of course in every research it’s something we shouldn’t forget about. You can do the best survey, you can run the best interviews if you, if you do a bad analysis of it at the end. But I think in surveys it’s even easier. You don’t clear your data, you don’t realize if someone put in Like data cleaning can be simply that you check their answers and you realize that if they answer this, they cannot answer that because they are contradicting and then you need to delete the whole row because it’s something like was wrong there.

So if you don’t clean your data and you don’t really go through the like properly, you don’t evaluate it properly, the open questions, which is always a serious pain to evaluate that with a lot of response. So you can, again, even if you had good questions and good options, you can still evaluate it at the end to turn it into what you want to see.

And I don’t know how your government do that, does these kinds of things, but at least in my country, it happens very often that they, they kind of evaluate things in a way that seems the best for them, just to approve what they wanted to hear. That’s always a danger.

[00:31:03] Tina Ličková: So when we were talking about what to do or how to do surveys, you were mentioning always starting with interviews.

Arguing even with stakeholders about a value of it, also looking into our notes, thinking twice if you really need a survey, but I’m fascinated by the fact how much you dislike pie charts.

[00:31:26] Zsuzsa Kovács: Pie charts are the worst.

[00:31:30] Tina Ličková: Why is that? Why you are not in favor?

[00:31:33] Zsuzsa Kovács: It’s not me, actually. It’s like serious scientists or like data people who, actually there are a lot of articles and it’s fascinating because you never come across and then if you Google what is wrong with pie charts, you will get like dozens of articles.

I think my favorite, the only proper pie chart is when, you know, you have a pie and one part is missing and it says pie eaten, pie not eaten. That’s the only proper pie chart. So, the problem with it is that. The biggest problem is that you, it’s really hard to read that. So the same information provided in a pie chart versus a bar chart, you don’t really, you cannot compare the different sections of it.

And it can be really misleading. And I think many times people actually use that. If you kind of want to manipulate these kind of things, pie charts will be your friend. Because if you put two pie charts next to each other, You can’t, like your brain cannot really understand and compare the different sizes.

If you have a bar chart, it’s simple. This is like, you know, it’s much higher, but in a pie chart, it’s very hard to understand. And it’s also lacking a lot of information that should be there. So don’t use pie charts, always go with bar charts. I know they are not so sexy and yet it doesn’t make it better.

If it’s a donut, they’re like, that’s the same family. Forget about it. Go with bar charts, even if they are boring, but they communicate much better, the things they want to. Yeah, communicate.

[00:32:54] Tina Ličková: I have to admit, I didn’t know the thing about PyChart, so thank you for saying that, but also thank you for sharing all the five and plus no gos, because that’s very big of a value.

Is there something that you didn’t have a chance to tell us?

[00:33:10] Zsuzsa Kovács: Yeah. One thing now that you asked, I think a researcher’s job is not only to bring insights to the product development and to the stakeholders, but also to, to raise empathy. This is also a big part of design thinking. And you cannot do that with surveys.

It will be just a row. It’s totally inhuman. You cannot feel empathetic to a row in an Excel sheet. No way. But if you have interviews, You can do snippets, you can drag your stakeholders or your developers to interviews or to usability tests, and it will do great change. One of my favorite stories is. We had a bug in, in the Prezi app and I ran into it all the time in all of the usability tests and I begged the developers to fix it and they always said that’s a technical limitation.

We can’t do that. I was really fed up. And then we had a, we tried to invite as many developers to sessions as we could and they started to come to the usability sessions as well. But still not all of them. Yeah. And then once we did that, it was viewing parties is what we tried. I read an article that sometimes you can get your developers come to the sessions, cut out the most important, you know, pieces from the interviews or the usability tests and show it to them.

And that’s when I did, I even brought popcorn. It was a huge success among developers. They loved it. And then what I did is. I cut out this one particular piece from three or four usability tests. When the user is struggling with the button that is not working, I made them watch it. And it was shameful for them.

And they felt so bad that this is really what they did, is that they fixed it for the next day. So there was no technical limitation anymore. This is what I did. If you see a real life person struggling or you hear a real life person explaining something, it can change so many things. A line in an Excel sheet have never changed anything, I believe.

Erika Hall also has a brilliant, like, she has great articles on Medium. I recommend you to follow her. She wrote an article on surveys and one on focus groups as well. What is the problem? Why you shouldn’t do that? So please go there and read them. And the NPS is a whole, that’s, we shouldn’t even go there.

That’s another like huge area, which is the most common survey actually, and it’s not better than the rest. Yeah, I think, yeah, don’t do surveys, please. If I can ask you one thing, do interviews instead. You will learn much more. You will meet amazing people, very nice people explaining their domain or their problems or things around their lives.

[00:35:43] Tina Ličková: I will just add two things.

About NPS, there will be another episode where we go on and, yeah, swear.

Good. Good. Looking forward to it.

The second thing is that we are planning a webinar with you in the future. So everybody is welcome because I know, I think you have a lot to share and thank you for sharing this episode with us.

[00:36:05] Zsuzsa Kovács: Thank you for inviting me. It was really fun.

[00:36:12] Tina Ličková:

Thank you for listening to UXR Geeks. If you enjoyed this episode, please follow our podcast and share it with your friends or colleagues. Your support is really what keeps us going. If you have any tips on fantastic speakers from across the globe, feedback, or any questions, we’d love to hear from you too. Reach out to UXR Geeks podcast at UXtweak. Thanks for tuning in.

💡 This podcast was brought to you by UXtweak, an all-in-one UX research tool.